Music started to be written down in books in the early ninth century AD. At that time, most of Europe was under the influence of the Carolingian Empire, and a tradition of Christian liturgical chant–known today as ‘Gregorian’ chant–began to emerge. It was possibly to ensure the transmission of a more uniform repertory of music throughout the various regions of the empire if musical notation was first developed in the West. However, only fragmentary evidence survives from that period; the earliest complete books date to around the year 900 AD.

The purpose of manuscripts of liturgical music was to remind the singers of the melody for a particular chant–a melody that they likely knew already mostly by heart. This is why the first examples of music writing, neumatic notation, represent mainly the shape of a melody and only few other details for its vocal performance. Most importantly, however, early liturgical books were a way to ensure a coherent and stable performance of ritual, by fixing the order in which chants had to be sung, how they were interpolating lessons and prayers, as well as an authoritative version of their text.

Chant found its way into books gradually, making use of the blank space already available on the page, and eventually became an integral part of most service books. This is perhaps one of the main distinctions between manuscripts preserving liturgical chant–’music in books’–and the later collections of polyphonic compositions–’books for music’.

Magdalen College preserves some remarkable examples of manuscript fragments, recovered in book bindings from the Old Library the over the last two centuries. Their date ranges from around the year 1000 to 1500 AD. Unfortunately, very little evidence survives of books used in the College medieval Chapel. This lacuna is likely to have been the result of the 16th c. Reformation, together with the gradual replacement of manuscript service books with printed ones.

Fragments of liturgical books are by far the most common type among surviving medieval manuscript fragments. The daily performance of liturgy in the Middle Ages required a constant production and use of manuscript volumes, which resulted in the wearing out and rapid consumption of this material. Exceptions are those liturgical manuscripts that were commissioned to serve more as objects for display, rather than of use; such manuscripts were normally kept safe in a monastic library, or even as part of the treasure of a cathedral, and are often the ones to survive intact.

Possibly France, 11th c., first half.

This fragment of a missal is the oldest piece in the liturgical fragments collection. Right at the centre is the Gradual Deus vitam meam, with its verse Miserere michi domine, that was sung between the two lessons. Chants were usually written in a smaller script than other texts, like the lessons or rubrics, and in this case red lines were used to connect the syllables of the chant text where long melodic phrases had to be sung. However, while space was left for musical notation (neumes), this was never added.

MS Lat. 271, f. 36

England, 12th c., second half

This almost complete bifolio contains a number of tropes for the Kyrie eleyson and the Gloria in excelsis. Tropes were textual, and often also melodic additions to pre-existing chants. Because chants like the Kyrie and the Gloria had fixed texts, tropes were used to render them more specific to certain feasts, in this case for a Mass of the Virgin Mary.

Add. 98, f. 2

An ‘everyday’ service book like a missal, a breviary or an antiphonary, was, instead, very frequently reused as binding material. However, wear was only one of the possible reasons for reuse; changes in decoration styles or scripts being also other common factors. As far as music is concerned, it was frequently the development to more advanced systems of musical notation, as well as changes in the repertory – like the introduction of new chants, or the suppression of others for institutional or cultic motives – that caused the manuscripts to be discarded and their parchment to be reused.

England, 13th c., first half

Despite having been used as binding material, this fragment preserves almost the entire extent of the page, giving a close idea of the original volume and its format. The folio on display contains the Mass for Easter Day. The initial of the introit Resurrexi (‘I have risen’), the first chant of the Mass, is in an elaborate English decorative style. The second lesson, on the verso, is taken from the Gospel according to St Mark and it opens mentioning Mary Magdalen bringing spices to the sepulchre.

MS Lat. 265, f. 72

England, 14th c., middle

These two fragments of a processional came from the binding of a lavishly illuminated 15th-century French Book of Hours, and contain the directions, written in red ink, for the performance of processions – according to the Sarum use – on particularly important feasts, like St Stephen [f. 45] and St Sylvester [f. 48]. The original volume was rather small in format so that it may have been carried in the procession.

MS Lat. 265, ff. 45, 48 [from MS Lat. 5]

England, 14th c., middle

A copy of Laurence Humphrey’s Optimates (Basel: J. Oporinus, 1555); carrying a fragment of a 14th century English processional with musical notation. Magdalen College’s copy of President Laurence Humphrey’s mid-16th century work on nobility was likely bound in Oxford, where the leaves of a 14th century processional were added to the front and back boards. The practice of adding parchment waste was structural, but in this, and many others cases it was likely an aesthetic choice as well.

Old Library, Magd. Humphrey-L (OPT)

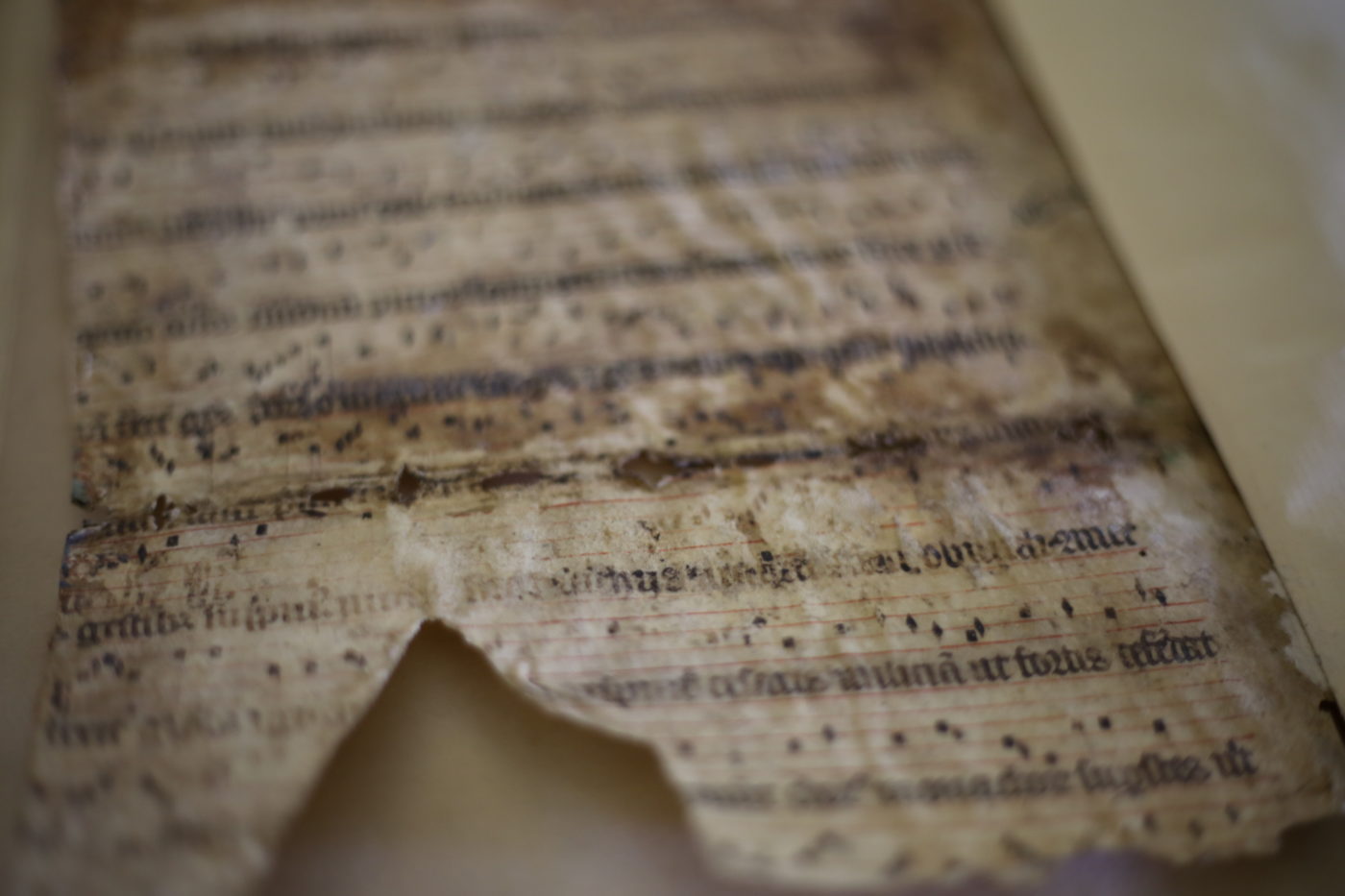

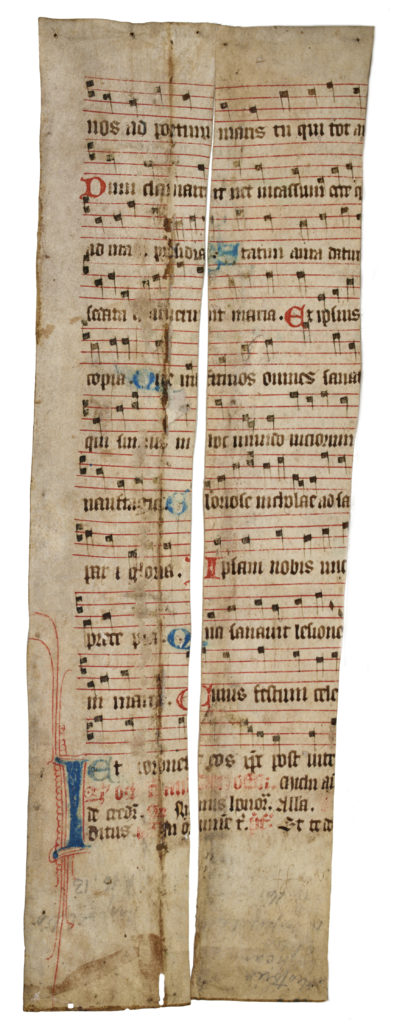

Missal ➻

Missal ➻England, 14th c., first half

Two strips coming from a notated English missal containing the sequence (a chant sung after the Alleluia) from the Mass for St Nicholas. Red and blue are use alternatively for each verse initials. The square notation is on a four-line red staff. The centuries of use as binding material distorted the parchment now preventing the strips to match precisely.

MS Lat. 266, ff. 82, 86

England, ca. 1400 or first half

It is not unusual for fragments coming from the same original manuscript to be reused in two different bindings and cropped accordingly. In the case of this missal, the larger fragment gives us the original dimensions of the page, which allow us to reconstruct the position of the other two. Here, the presence of music was restricted to those chants sung or intoned by the priest, as is the case of the litanies in the bottom right corner, or of the ‘cantillation’ of prayers in the opposite one. In the top-right fragment two rusty holes from the chain that used to be attached to the book in the medieval College Library are also visible.

MS Lat. 270, ff. 16, 17a-b

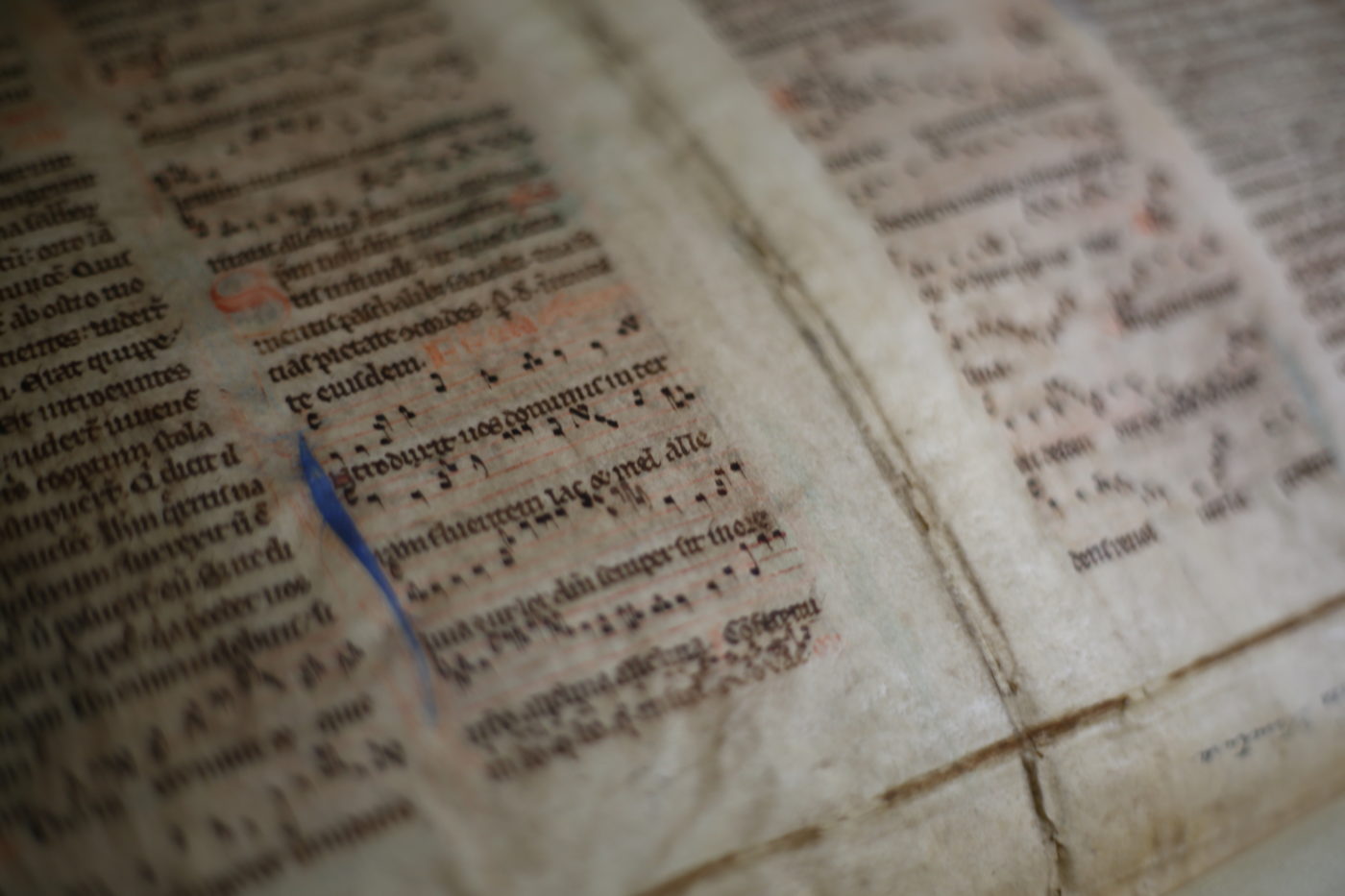

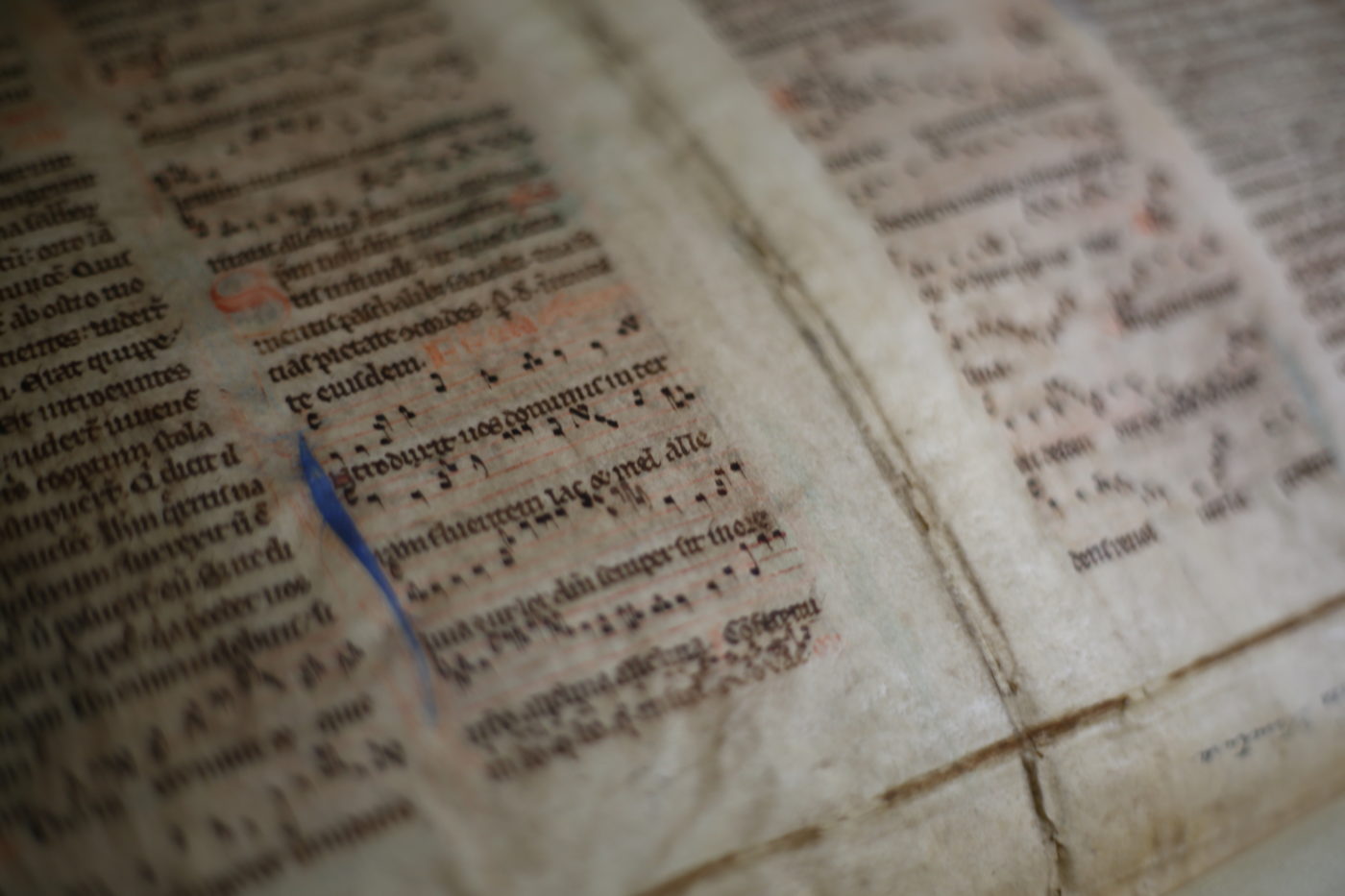

England, 14th c., first half

Two strips coming from a bifolio containing the text of St Matthew Passion, sung by the priest on Holy Friday. Musical notation was added in the interlinear space by at least two hands – one in red, and one in brown, the latter visible only on the verso – as a guide for the singing of intonations and cadences, respectively at the start and the end of a sentence (cfr. Petrus… in atrio; Et egressus… amare).

MS Lat. 266, f. 81

England, 15th c.

This fragment used to be part of the binding of a manuscript owned by Richard Lichefeld, Archdeacon of Bath and sometime principal of Neville’s Hall (now Corpus Christi College), who died in 1497, and whose name, possibly an ex libris, can be read at the top of the leaf. This piece of information may reveal that the original manuscript from which the fragment came (now Magdalen MS Lat 183) had a rather short existence, the script dating to shortly before its reuse as binding material. It is possible that this leaf may have been copied by a professional scribe – whose atelier was often also a bindery – and soon discarded, perhaps upon realising that musical notation, for which space was left, was not necessary for this text.

MS Lat. 267, f. 55

Processional ⇒

Processional ⇒England, 14th c., second half

One strips coming from a notated English Processional containing the prose for the procession on the vespers of St Stephen day. The choir would respond to each verse sung by the deacons by singing the same melody on the letter A, as reminiscence of the long flourish at the end of the word Alleluia.

MS Lat. 266, f. 90

England, 14th c., first half

The high grade of the original missal is revealed the by the now-fainted gold of the decorated initial for Lex domini irreprehensibilis, the introit chant for the Saturday of the second week in Lent, which would have been sung at the start of the Mass, as the celebrants and the choir reached the altar. The left-hand column contains the last two chants of the Mass on the previous day: the offertory, here incomplete, which was sung while the bread and wine were brought to the altar, and the communio, which would have been sung, instead, when the bread and wine are consumed.

MS Lat. 267, f. 48

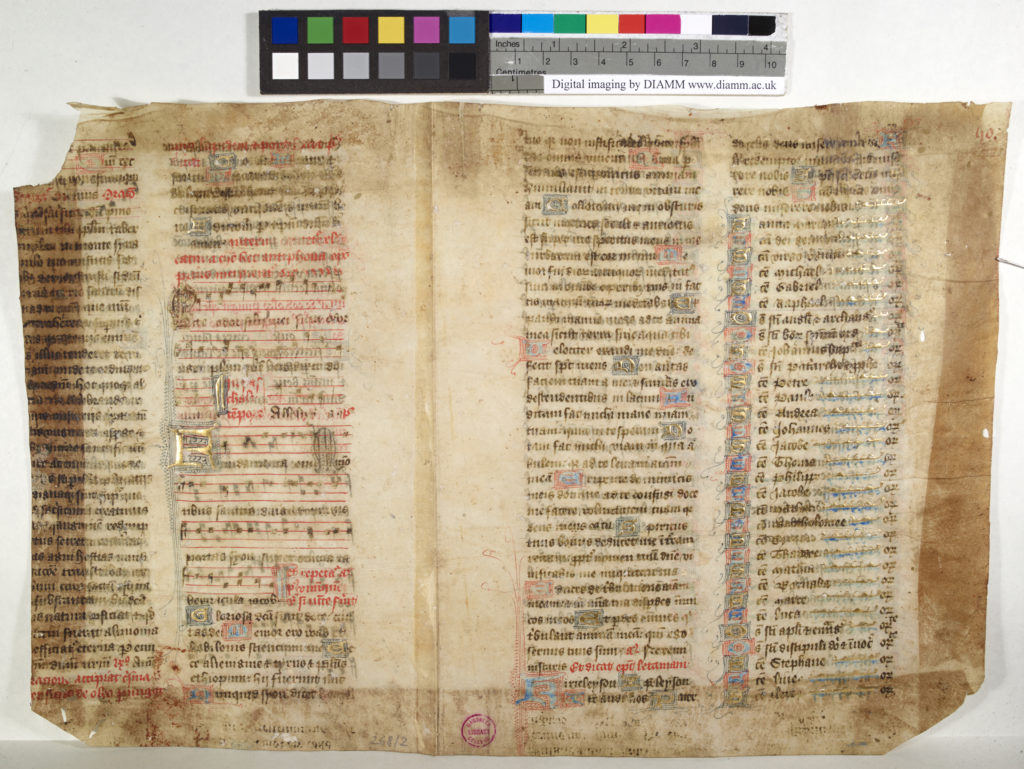

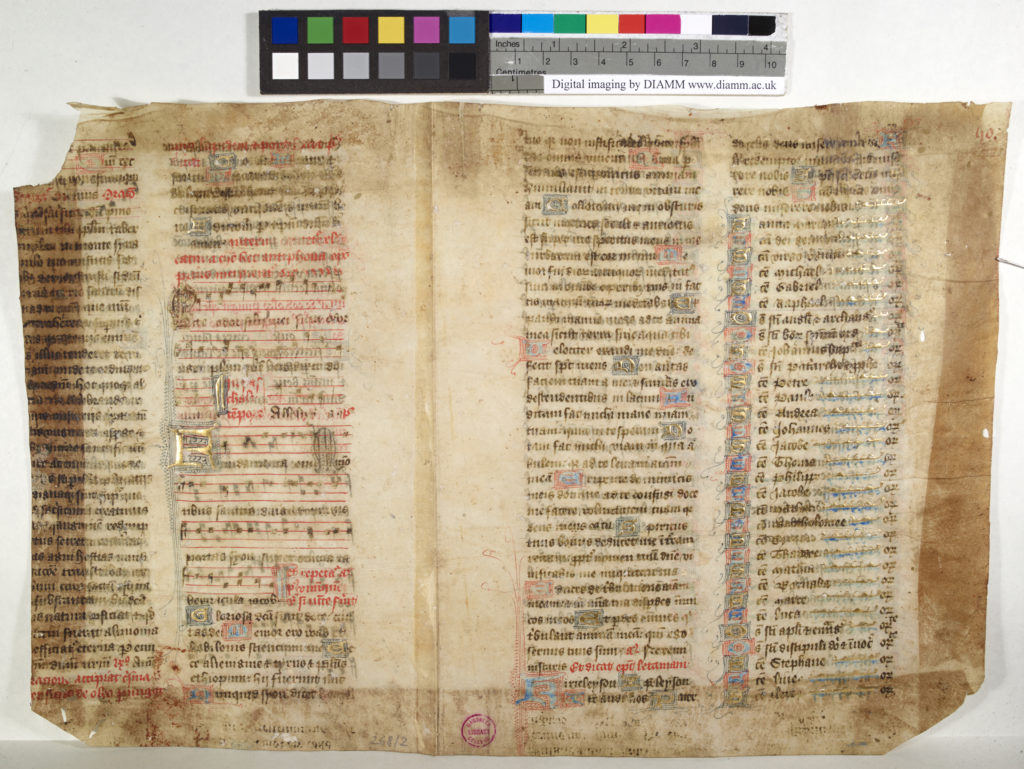

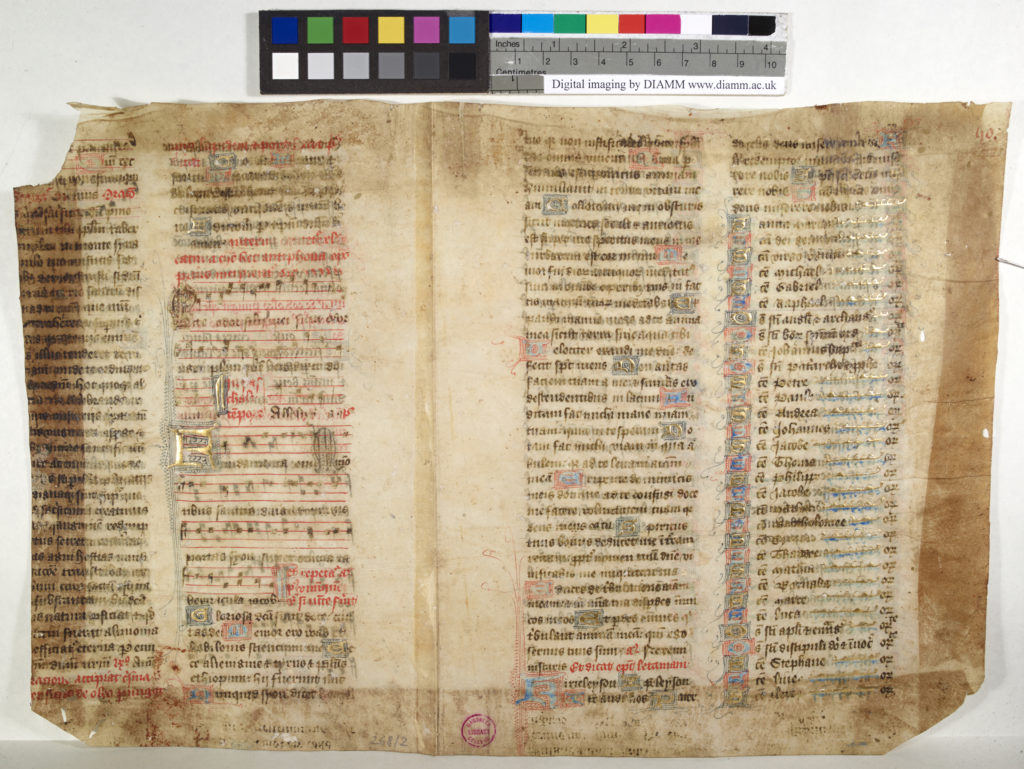

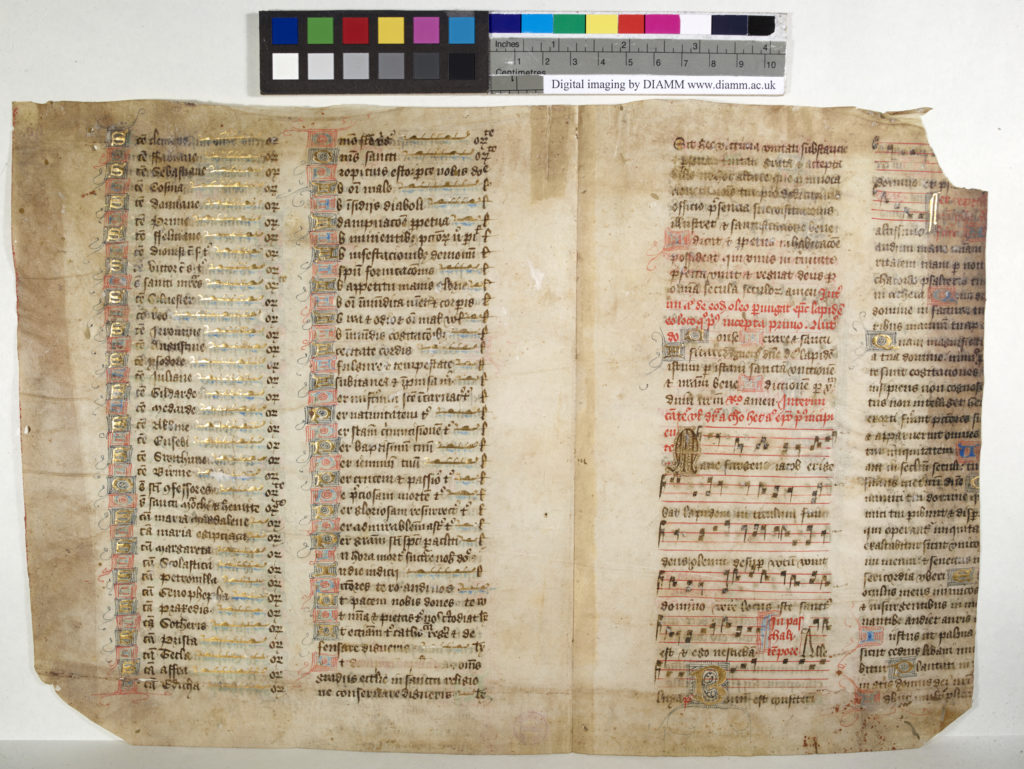

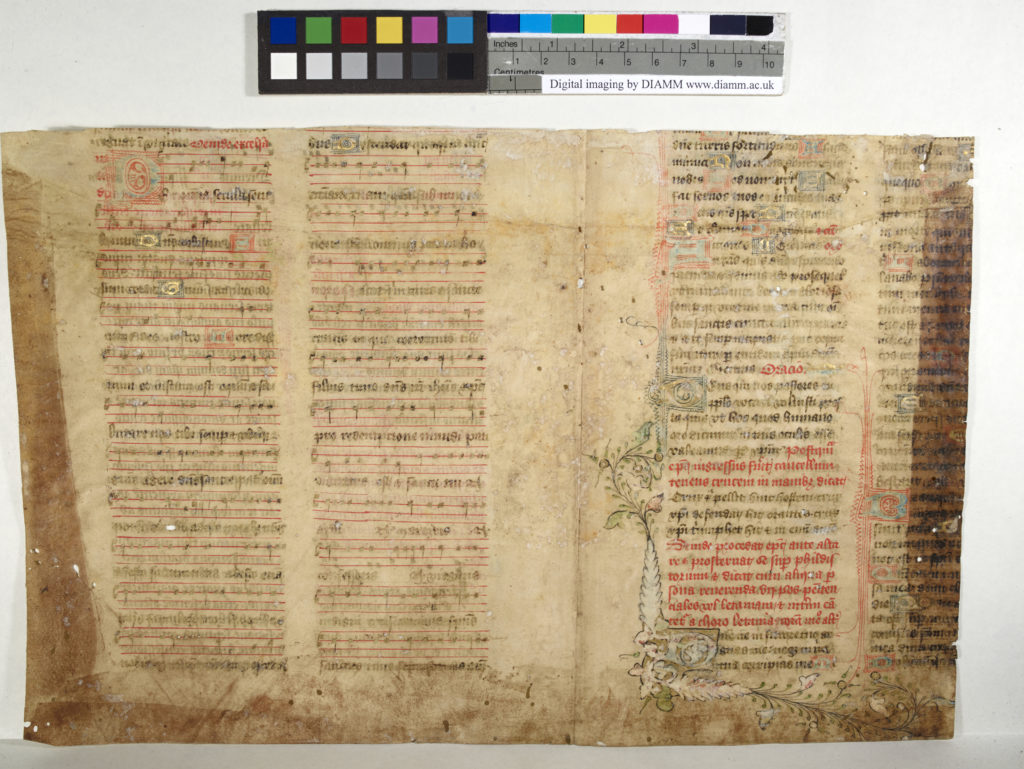

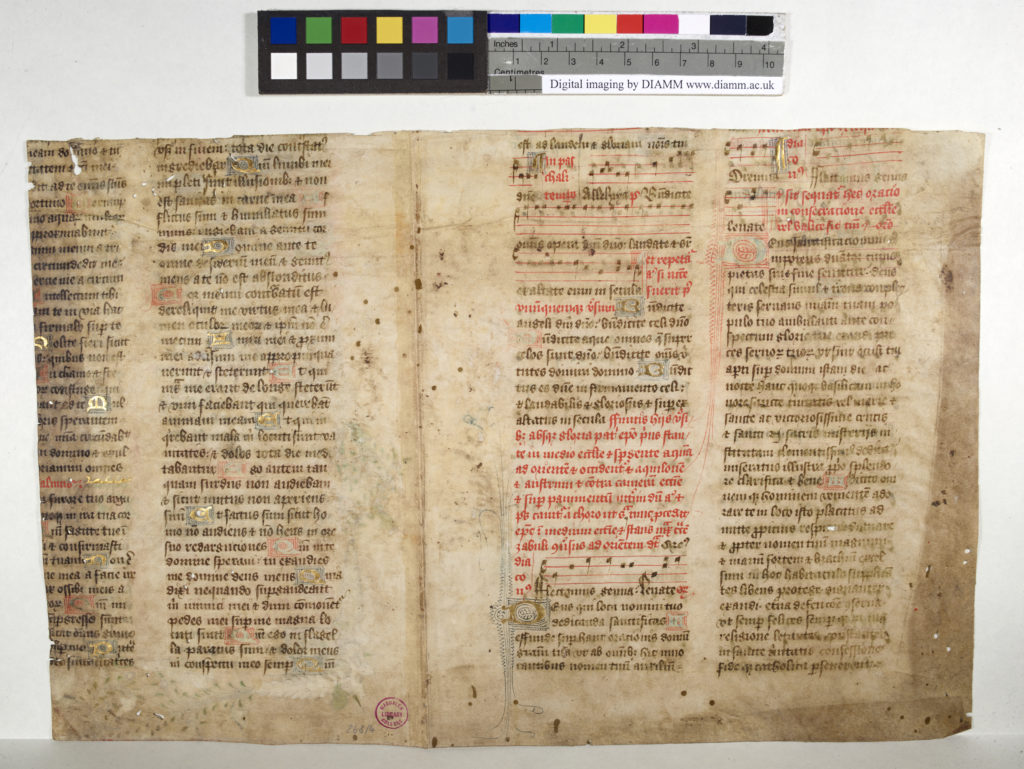

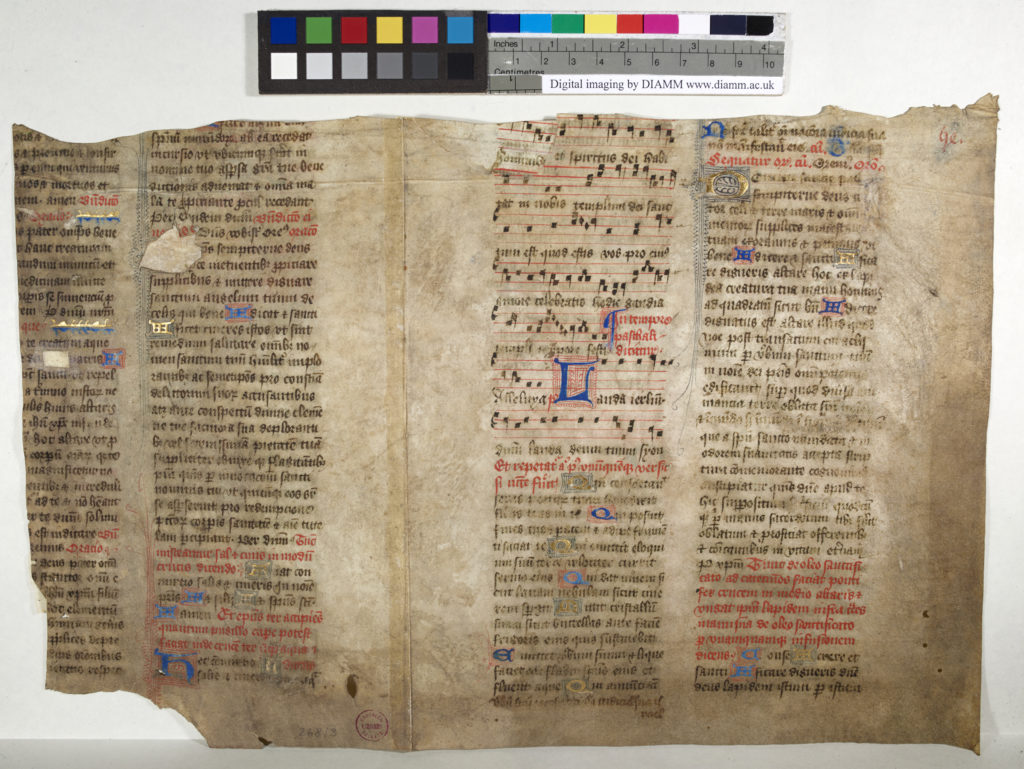

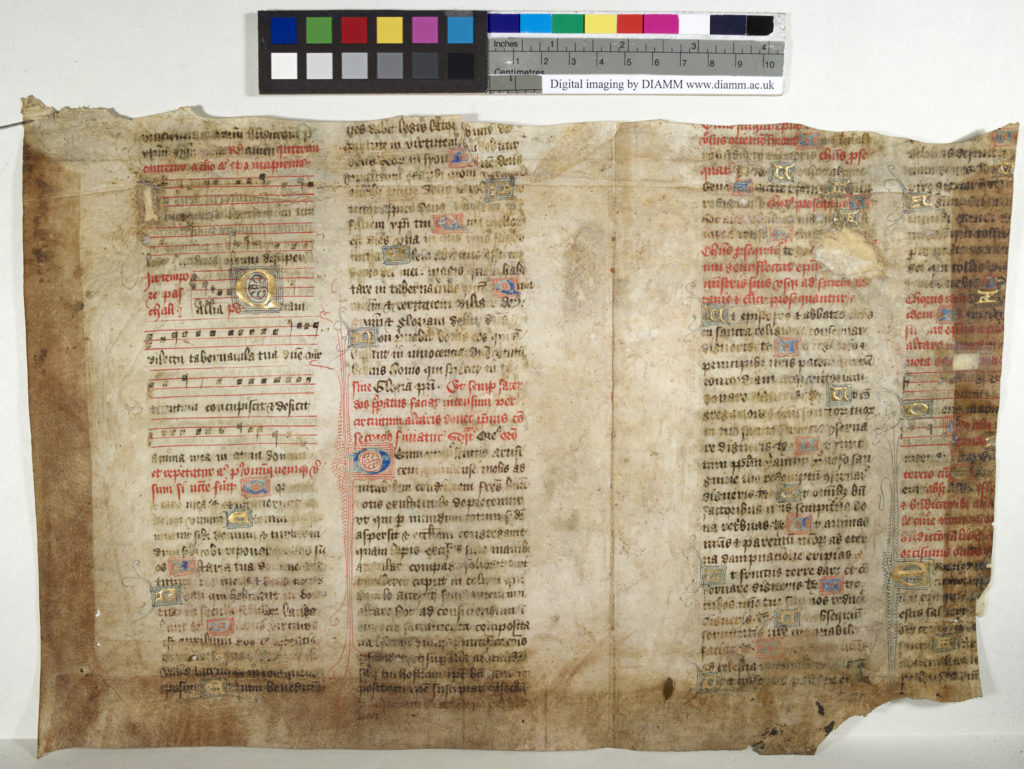

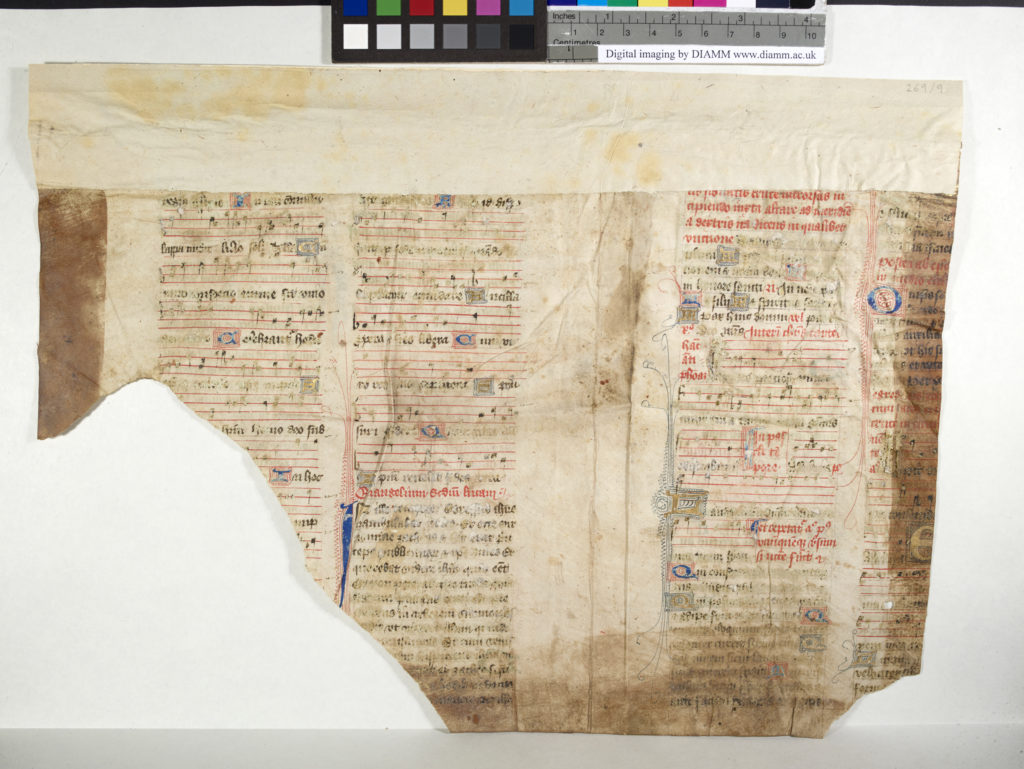

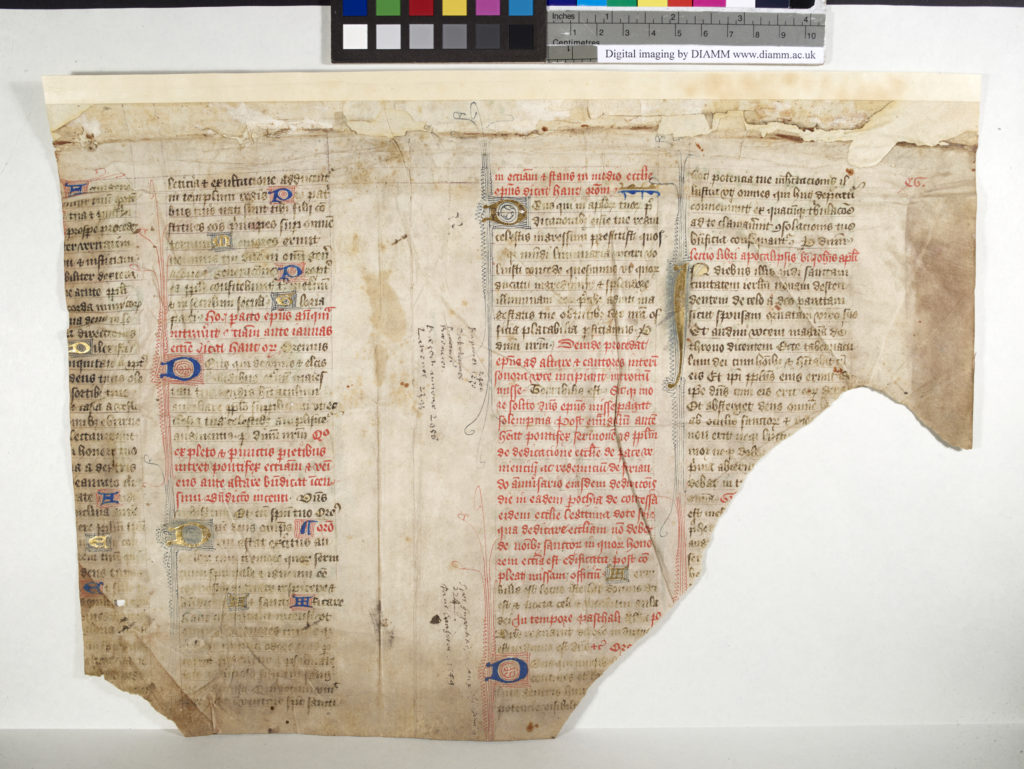

England, 15th c.

The pontifical is a book containing the texts for services performed by a bishop outside Mass and the Divine Office, like the dedication of a church, ordinations, blessings of sacred objects, and the crowning of monarchs. Chants are sung as part of these ceremonies, although often their performance was by trained cantors, rather than the bishop himself. Yet, music was nevertheless added as an important component of the liturgy, for those chants intoned by the bishop, as well as to confer the book a more complete and authoritative status. These four fragments (bifolia) are the most substantial group coming from one single original liturgical manuscript, a beautifully-illuminated pontifical, containing the service for the dedication of a church. Judging by the decoration, still visible in particular for the Litany of the Saints including blue with red foliate and gold leaf flourishing, the original destination of the manuscript must have been a see of some prestige.

MS Lat. 268, 2-4; MS Lat. 269, f. 9

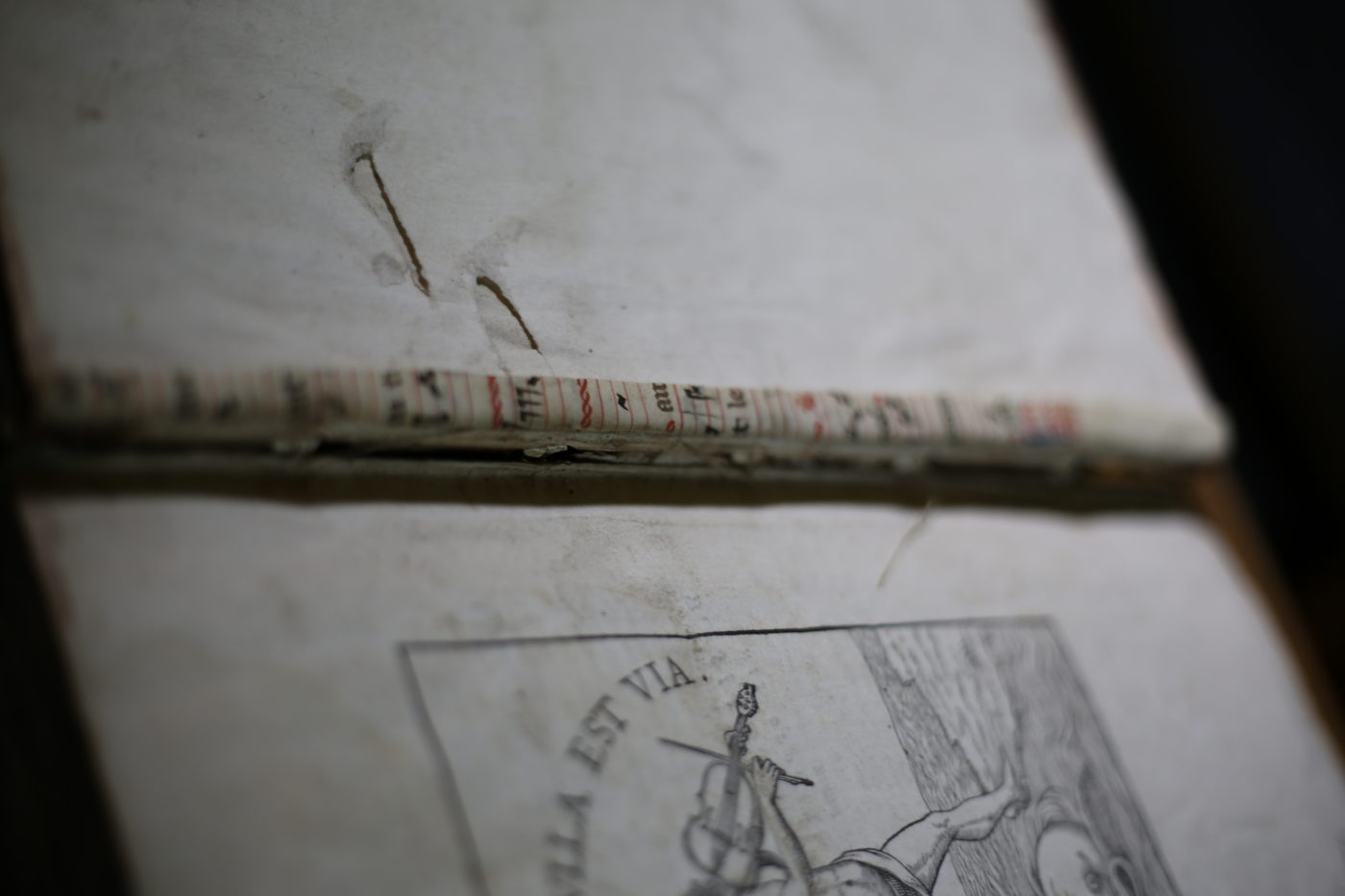

England, 13th c.

A strip of parchment from a book of liturgical music was used as quire guard (i.e. protecting a folded gathering of printed paper) in the binding of a copy of John Bale’s Scriptorum illustrium Maioris Brytanniae, printed in Basel in the 16th century.

Magdalen College Library, A.17.3

England, 15th c., first half

Two entire leaves, that once used to be part of a rather large antiphoner, have been used as a two-layered wrapper for a 16th-century copy of the College Statutes. This antiphoner is thus very likely the earliest example of service book that can be connected to music and liturgy in the medieval College Chapel

MS. 279